30th Sep, 2021 19:00

Modern & Contemporary Art

86

David Goldblatt (South Africa 1930-2018)

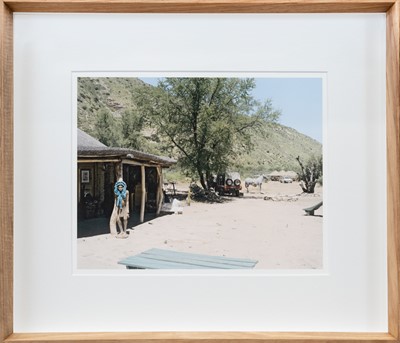

Untitled (Gamkaskloof)

digital print in pigment inks on cotton rag paper

Artwork date: 2006

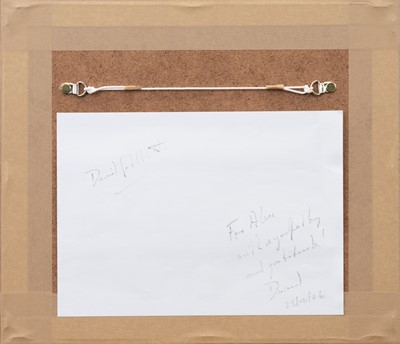

Signature details: signed and inscribed on the reverse

Sold for R34,140

Estimated at R30,000 - R40,000

digital print in pigment inks on cotton rag paper

Artwork date: 2006

Signature details: signed and inscribed on the reverse

(1)

image size: 18 x 23 cm; framed size: 33.5 x 38.5 x 4.5 cm

Provenance:

Private collection, Cape Town. Gift from the photographer.

Notes:

This lot is accompanied by a copy of David Goldblatt: The Last Interview (2019). The author of the book joined the photographer on a trip to Die Hel (where the photograph was taken) and was gifted this unique photograph. A different size and edition of the image was exhibited at Stevenson Gallery in 2008 as part of the exhibition Intersections Intersected, which showcased works photographed by Goldblatt before and after the fall of apartheid. The editioned print included in the 2008 show is titled At the food-shop and restaurant of Annatjie Mostert-Joubert, during a kultuurfees. Annatjie is a daughter of Gamkaskloof and the only member of the original community still living there. Gamkaskloof, Western Cape, 27 October 2006. Its image size is 99 x 127 cm.

Below is a piece of writing by the seller (originally published in the Mail & Guardian newspaper) chronicling their time with the photographer on the trip where he photographed the image presented in this lot:

By the time we reach the top of the Swartberg Pass, the duelling banjo soundtrack from Deliverance, John Boorman’s 1972 cinematic tale of an ill-fated canoe trip up the Cahulawassee River in deep backwoods America, has started playing in the back of my nauseous mind. I’m in a camper van turbulently winding its way over the rocky dust road that leads through a post-apocalyptic landscape to a valley deserted by its occupants back in the 1970s.

At the helm of the vehicle, driving at the age of 76 like he’s in the Paris-Dakar Rally, is photographer David Goldblatt. Sitting alongside him armed with a brown paper packet filled with rusks, dried peaches, biltong and cashew nuts is his wife, Lily. We’re on our unpaved way to a place called Die Hel and all my good intentions have been overcome by the primitive violence of the landscape.

Hulking boulders have been tossed across the plains as if God once threw an almighty tantrum here. It should by all accounts be the soundtrack to 2001: A Space Odyssey that I’m hearing, but it’s those Deliverance banjos that I can’t get out of my mind; bluegrass banjos and red necks, accordions, Mausers and creepy thoughts about what happens to a community when it isolates itself from the rest of the known world for over a century.

The Klowers, as they are now known, were a group of highly resourceful and doggedly independent farmers descended from a group of Afrikaners who trekked inland in the early 1800s and settled in this isolated valley, hacking through the thorn trees and rugged bush to cultivate their land. Through sheer willpower they turned this stony desert landscape into a fertile oasis bearing grain, citrus fruit, tobacco, figs, grapes, pomegranates, plums, pears, walnuts, almonds… But that’s where the diversity ended. Their only contact with the outside world took place when they trekked through the Swartberge with a caravan of pack donkeys laden with their hard-won produce stuffed into 50-pound sacks to barter in the nearby Karoo towns of Calitzdorp and Prince Albert.

The hairpin road, built as the result of a Volk-en-Vaderland-style whim by a National Party administrator, took Oom Koos van Zyl and his team of 12 workers two and half years to complete. An engineering feat of note, it was opened on 21 August 1961 to a small chorus of glee, but signalled the beginning of the end. By the mid-Seventies the community had packed their goods and trekked off along that road, leaving behind them only the haunting relics of a lost world, a strange Karoo Atlantis for the speculations of latterday tourists in their meaty four-by-fours.

Goldblatt greets my barrage of curiosity with patient bemusement. No, he tells me, there were no overt signs of inbreeding… Instead he speaks of the Marais, Nel and Cordier families with the affection of a long lost cousin and his excitement mounts along with my dread as we begin our precarious descent into the cursed and blessed valley of Gamkaskloof.

Goldblatt first visited this place in late Sixties, and photographed the families who lived there as part of an extended photographic essay on Afrikaners, which led to the publication of Some Afrikaners Photographed in 1975.

‘At the end of 1966, the beginning of 1967, I went into the Karoo and Western Cape, and made a similar journey the next year, accompanied by Lily. We had a pup tent, sleeping bags and primus stove, and camped, very often, by the side of the road. Travelling through vast, sparsely populated parts of the country with my camera became a major part of my life at that time. I think that our landscape is an essential ingredient in any attempt at understanding not just the Afrikaner but all of us here,’ reads Goldblatt’s statement pasted onto the wall at the entrance to the Michael Stevenson Gallery in Cape Town, where the exhibition Some Afrikaners Revisited is currently on show.

In 2004, Goldblatt revisited Gamkaskloof. When he returned home he looked again at the images he’d done there in the Sixties and realised that there was quite a lot that he’d left out of the 1975 book, which is today a much sought-after collectors’ item. ‘It seemed sufficiently interesting to merit publication now, particularly since that group of highly independent farmers had completely disappeared,’ reads the statement. That decision led to the current exhibition and a new book containing all but one of the photographs reproduced in the 1975 book, as well as 20 additional photographs taken at the same time. The book, published by Umuzi, will be available early in 2007.

As the camper sloshes and crunches its way across a rocky riverbed, Lily asks David if this was the crossing where they found the predikant. ‘What predikant?’ I holler from the back and my question merits the first in a host of splendid tales of a time gone by. ‘When I came here in 67/68, Lily was with me in the Peugeot 403,’ says Goldblatt, never one to forget a detail. ‘Because there was so little traffic – one or two bakkies a day – I had parked on the road and was busy photographing. Suddenly I hear loud hooting and there’s a huge Ford with big tail fins and behind the wheel an obese man in a vest sweating profusely and his wife and brood of children. I waved to him and apologised and moved the car, and he drove through in a cloud of dust.

‘Anyway, that evening I worked until quite late. It was sunset before I’d finished and he’d passed us on the way out. When we eventually pulled out, we came to one of these riverbeds, which was completely dry, drought stricken. And he was sunk to his axels in the little round river stones. He was completely stuck and was sweating and pushing and trying to move the car, and revving it up and just making it worse. So I stopped…

‘Lily went and sat on the riverbank with his wife, who told her about her hysterectomy and so on, and this guy and I jacked up each wheel separately, put brushwood underneath and moved the car forward a few inches, did the same again and again until eventually we got him out at about half past eight that night. While working together, he told me that he was the predikant from the NG Kerk in Welkom. So when we’d finally got him out and he’d resettled his family in the car and he was at the wheel, he said: ‘Meneer Goldblatt, ek is baie dankbaar’ [I am very grateful] en ek sê for hom: ‘Dominee, nie te danke nie. Dis seker die eerste keer wat a Jood a dominee van Die Hel gehelp het.’ [No trouble, Minister. This has to be the first time a Jew has helped a minister from Hell.] And he took that in good spirit.’

We arrive in Die Hel to a small hive of preparatory activity around the central restaurant/kiosk at the entrance of which is the unsettling image of two wooden sculptures of naked San trackers upon whose heads lace-adorned Boere kappetjies [bonnets] have been unceremoniously plonked. A harmless joke in Noddyland perhaps. In the context of several centuries of colonial conquest followed by a half century of apartheid I’m not so sure. But subjugated San spirits aside, the vibe is welcoming and upbeat. The inaugural Gamkaskloof Kultuurfees kicks off tomorrow and there are enough policemen camped outside Annetjie Mostert Joubert’s house to quell a small riot. Luckily though they seem more interested in the fire and the company than in crowd control and, at this stage, the crowd comprises a harmless minority of three.

We make our way to Tant Lenie’s house, a basic but beautifully crafted, thatch-roofed homestead that quietly recalls the inventive spirit of Helen Martin’s Owl House at Nieu Bethesda. It’s in this humble building beneath the pure blue Karoo sky that Goldblatt’s images are being hung by Andrew da Conceicao from Michael Stevenson gallery, who jokes that he was despatched from the Mother City with the words ‘‘It’s not the Museum of Modern Art. Make it work.” Of course, there’s not a frame out of place. It might as well be the MOMA. And the irony is that Goldblatt was the first South African to be given a solo there in 1998.

As a photographer, he has devoted more than half a century to capturing the unspeakable essence of what it is to be a South African – more than that, what it is to be human. And the world has sat up and taken notice. His retrospective, David Goldblatt: Fifty-one years, toured galleries and museums in New York, Barcelona, Rotterdam, Lisbon, Oxford, Brussels, Munich and Johannesburg between 2001 and 2005. In July this year his work was the subject of a retrospective at the Rencontres festival in Arles, France. Later this month he’ll be travelling to Göteborg Sweden to receive the prestigious Hasselblad Award in recognition of his lifelong achievements.

And here he is, in his khaki shorts, boots and socks, sticking Prestik to the back of laminated posters and making a small correction on each one with a marking pen. Everything must be right. The smallest detail matters. And seeing the images of Ella Marais combing her hair and Lewies Nel listening to Jeremy Taylor’s ‘Ag Pleez Daddy’ on a battery-powered turntable hanging right here in Tant Lenie’s voorkamer, it occurs to me that these images of Goldblatt’s have, after three decades in the ether, come home.

Night falls on the valley and we gather in the voorkamer of Freek and Martha Marais’ house around dinner and a bottle of vinegary Merlot bought in Laingsburg. It’s too early for ghost stories, but there is something eerie about being in these rooms, in this very house. These are the rooms in the pictures; the lived lives transmogrified into two-dimensional immortality. But the souls who inhabited these rooms have moved on. The patina of everyday life on the old stone walls has been covered over with fresh acrylic paint.

But the kitchen is the very kitchen with the same brandsolder ceiling in which Goldblatt photographed the man and the boy back in 1967. The can of BP motor oil and the box of Radion detergent are long gone now, along with the fly strips covered with hundreds of little black fly corpses. But the old stove is still there and the little window through which the light still pours in.

Goldblatt tells us that the bedroom next door to the kitchen, in which he and Lily will be sleeping, is the very room in which he photographed Ella Marais combing her long blonde hair. “She was a young girl on the cusp womanhood then,” he recalls. “I photographed her with her sister Betty, playing in their father’s dam and on a see-saw.” He goes on to tell us that he discovered from Annetjie Mostert Joubert that Betty was in an accident that left her brain damaged and that Ella, whose marriage ended badly, has spent the rest of her life nursing her incapacitated sister in Pretoria. In Goldblatt’s image none of that has happened yet. No harm has befallen Ella. She’s just a pretty young girl innocently combing her long blonde hair.

Goldblatt’s deep sadness is tangible. And there’s something in that sadness that solves a riddle for me. I’ve often wondered about the willingness of his subjects to give themselves over to him so completely. It’s that nakedness in his images, that innocent sense of trust in the author. I’ve often wondered why. Why no reserve? Why no fear of betrayal? I think I understand now. Because that fear was never necessary.

There are no ghostly visitations in my sleep. No spooky banjo sounds. Only the still dark Karoo night and the eternal mystery of the relationship between the photographer and his chosen subjects.

You can place an absentee bid through our website - please sign in to your account on our website to proceed.

In the My Account tab you can also enter telephone bids, or email bids@aspireart.net to log telephone/absentee bids.

Join us on the day of the auction to follow and bid in real-time.

The auction will be live-streamed with an audio-visual feed.

Auction: Modern & Contemporary Art, 30th Sep, 2021

Aspire Art Auctions brings a significant and insightfully compiled selection of top-quality modern and contemporary art to auction in Cape Town. The sale stars exceptional works by many of South Africa’s big signatures, including, William Kentridge, Robert Hodgins, Penny Siopis, Edoardo Villa, Sydney Kumalo and J.H Pierneef, amongst others. Also featured is an exciting collection of contemporary artists from elsewhere in Africa – Patrick Bongoy and Zemba Luzamba from the Congo, Moustapha Baïdi Oumarou from Cameroon and Gerald Chukwuma from Nigeria.

IMPORTANT NOTICE:

Logistics

While we endeavour to assist our Clients as much as possible, we require artwork(s) to be delivered and/or collected from our premises by the Client. In instances where a Client is unable to deliver or collect artwork(s), Aspire staff is available to assist in this process by outsourcing the services to one of our preferred Service Providers. The cost for this will be for the Client’s account, with an additional Handling Fee of 15% charged on top of the Service Provider’s invoice.

Aspire Art provides inter-company transfer services for its Clients between Johannesburg and Cape Town branches. These are based on the size of the artwork(s), and charged as follows:

Small (≤60x90x10 cm): R480

Medium (≤90x120x15 cm): R960

Large (≤120x150x20 cm): R1,440

Over-size: Special quote

Should artwork(s) be collected or delivered to/from Clients by Aspire Art directly, the following charges will apply:

Collection/delivery ≤20km: R400

Collection/delivery 20km>R800≤50km

Collection/delivery >50km: Special quote

Packaging

A flat fee of R100 will be added to the invoice for packaging of unframed works on paper.

International Collectors Shipping Package

For collectors based outside South Africa who purchase regularly from Aspire Art’s auctions in South Africa, it does not make sense to ship artworks individually or per auction and pay shipping every time you buy another work. Consequently, we have developed a special collectors’ shipping package to assist in reducing shipping costs and the constant demands of logistics arrangements.

For buyers from outside South Africa, we will keep the artworks you have purchased in storage during the year and then ship all the works you have acquired during the year together, so the shipping costs are reduced. At the end of the annual period, we will source various quotes to get you the best price, and ship all your artworks to your desired address at once.

Aspire Art will arrange suitable storage during, and cost-effective shipping at the end, of the annual period.

Collections

Collections are by appointment, with 24-hours’ notice

Clients are requested to contact the relevant office and inform Aspire Art of which artwork(s) they would like to collect, and allow a 24-hour window for Aspire Art’s logistics department to retrieve the artwork(s) and prepare them for collection.

Handling Fee

Aspire Art charges a 15% Handling Fee on all Logistics, Framing, Restoration and Conservation arranged by Aspire.